First and foremost, a little bit on the history of hair and its power. To quote Deborath Pergament from “It's Not Just Hair: Historical and Cultural Considerations for an Emerging Technology” (1999):

Hairstyles and rituals surrounding hair care and adornment convey powerful messages about a person's beliefs, lifestyles, and commitments. Inferences and judgments about a person's morality, sexual orientation, political persuasion, religious sentiments and, in some cultures, socio-economic status can sometimes be surmised by seeing a particular hairstyle.

What she means by that is that our hair, just like clothing for example, plays a significant role in how we perceive ourselves and others. Unlike clothing however, it is a part of our being that we cannot change at its core, even if there are countless methods to transform it temporarily. It is therefore a much more personal aspect of an individual than their clothing and carries a heavier emotional load, which grants it a status of significant importance with regards to our identity.

In other words, because of this emotional bond that we have with our (facial) hair, it reveals much about our character and person, whether that be our values, beliefs and views regarding politics, religion, gender/sexuality or our socio-economic status. These factors differ between cultures and as a result reveal plenty about an individual’s stance regarding the ruling culture’s beauty standards, and whether they are in a position to question the standards in the first place.

Many explanations are given as to why men and women have particular hairstyles in several different periods of time. These range from practical reasons like men in the army who were obliged to shave their head when enlisted, a practice already common during the Roman Empire, through the World Wars and still today. But let’s not forget this is a western way of combat preparation; Vikings, Samurai, Mongols, African warriors and Native Americans to name a few all managed perfectly well to fight with long hair. To them this often was and still is a sign of power and demand for respect, whereas short hair was seen as a sign of slavery, submission and loss of dignity. It is definitely more complex than that, but it shows how cultural background is highly important in considering customs regarding hairstyles.

Another reason often cited has to do with decoration or showing off status and wealth, for example during the 18th century when towering wigs were fashionable for both men and women in high society. Generally speaking, it does take time and wealth to be able to take care of long locks or to be able to afford elaborate wigs, which is why the lack of practicality has little to no significance other than to show exactly that: it was not an issue.

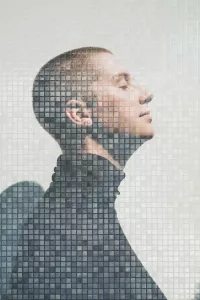

© Karolien Wilmots

Of course, politics plays a role as well. Most famous probably are the hippies in the ’60s when long hair for men was a sign of counterculture, and the afro’s in the ’60s and ‘70s rejecting western standards of beauty and superiority while honouring their own natural hair and culture in the process. The Rastafari philosophy continued this trend of anti-establishment and resonated with people from all kinds of ethnicities, even though today it is considered cultural appropriation if a white person adopts dreadlocks. All these are examples on how hair can be an indicator of a group identity as well. Religion can have that same effect, when it denotes for example marital status as is the case with the female married Orthodox Jews, who need to cover their hair as part of their modesty customs, or the Sikhs, who honour God’s gift of hair by not cutting it (facial hair included) and covering the hair on the head with a turban.

Restrictions imposed on hairstyle can be perceived as restrictions on our ‘being’ rather than a mere rule to follow. While regulations based on hygiene have their merit, often though they are based on a cultural perception of ‘cleanness’ and ‘professionalism’, which are embedded strongly but not always rational or useful. When power is abused to regulate how people should look, it can take forms of dehumanisation, degradation and humiliation. This happened in the concentration camps during WWII, where prisoners’ heads were shaved to break their resistance against tyranny and to erase their identity.

Now, what culture do you belong to? Think of its values, morals and vices. Is your culture the dominant one or is another one considered the norm where you live? In other words, are you free to express your own culture’s values or expected to comply to the ruling culture’s beauty standards in order to be accepted? And lastly, how important is it for you to comply to the standards to have a decent quality of life?

The answers you gave determine the degree of privilege and freedom you have to question amongst other things, the beauty standards of a culture. Whether or not you want to question them if you have the luxury to do so is personal and therefore entirely and solely up to you, but it shows the complexity of something as simple as hair.

All of this to provide a frame of reference for my personal choices. I am a Belgian photographer and writer, and I use both for introspection and reflection. Every one of these images are self-portraits, visually speaking one of my preferred ways of dealing with emotions and questions I can’t make sense of on paper. It is a slow process, confrontational and intense, and one that I am still discovering along the way, but it feels like the most honest way of creating. The images with long hair were taken a few days before I cut them off, the images with short hair were taken recently. I did this on purpose, to let some time pass between the two moments, to allow myself time to let it sink in and fully understand what the effect was on me.

With this series I don’t intend to provide a new philosophy on how to deal with beauty standards, it is not a call for action nor a critique on the system. It is merely a personal account of my journey in the hope that it will inspire reflexion and hopefully understanding. Whether that be for yourself, or for someone around you who has a different hairstyle than what you’re used to, pause to consider for a moment what the reasons could be for them to choose to stand out and deviate from the conventional. They may surprise you.

It has almost been a year since I almost ceremoniously shaved my head. I had two friends over who helped me do it – who were almost more nervous than I was - and to this day I haven’t regretted it for a minute. This has much to do with the build-up preceding the actual moment I decided to do it. I had always been the person with the long, sleek hair. Right before I turned 18, I dyed it red for the first time and continued to do so for eight years, working my way through a shorter haircut and growing it out all over again. So already once before I had cut my hair, but hardly as radical a cut as this one and it didn’t last very long. Back to long hair and it turned out that this coincided with many people’s fantasy idea of a foxy woman. This was rather personal information which they didn’t mind sharing with me at all – more often than not without consent. At first it flattered me, being desired does have a certain allure to it, but after a while it started to annoy me to the point where it became frustrating. It felt like even after getting to know me their fantasy hardly ever got updated to a more realistic idea of me, and it made me feel like to them I was a cartoon character ready to be lusted after whenever desired. Evidently this doesn’t apply to every person all the time, but it happened enough to cause discomfort.

As a result, I felt like my long red hair was my whole identity, a quite flat one too, and this bothered me profoundly. I am aware of the irony of this, because of course now I’m the person who shaved her head, but I will get back to this later. I wanted to be a person regardless of the state and colour of my hair. Another element that was on my mind was the idea that to voluntarily let go of my hair now meant that if I ever would have to do it because of illness, I could skip the feeling of powerlessness regarding my hair. So, I looked for a way to take back control, to create an identity that felt like my own again, with no links to my hair, and so shaving it off was the solution for me.

Funnily enough, once it was done, many people came to me to tell me I still looked good. The whole point was to do it regardless of their opinions - most people tried to discourage me beforehand actually - but once it was done it was as if they found comfort for themselves in telling me I needn’t worry; I was still desirable to them. I am aware that I am quite lucky for it to suit the shape of my head and facial structure. However, this time I felt in control. Because I had been ready to not be desirable to anyone, to just be myself, and that felt really powerful.

It was definitely a way for me to communicate something about my character, beliefs and values. If shaving my head now makes me the person who is referred to as that, so be it. It represents me more as a person than my long hair did. I do get responses from time to time on how it doesn’t leave people an option but to look me in the eyes, since they can’t really focus on anything else on my face while talking to me. That’s not quite a coincidence and it explains why I fondly call it my bullshit filter, because if they can’t deal with looking me in the eye, we probably won’t hit it off anyway. To allow myself to make eye contact a clear standard, to demand for that kind of respect, that has been one of the most empowering things I have done for myself. And so, when people ask me if I will let my hair grow again, I answer that I don’t think it will happen any time soon.